It has been a good November. And it is only half-way through! I have no doubt the rest of the month will be just as wonderfully packed with literary abandon. I thought I would share the first bit of what I have been working on this month. Here is Chapter One of Dreaded King. But two quick warnings. I am only about halfway through the tale which means I am still frantically typing away, and editing is not a large concern. Calling the chapter a rough draft is a nice way to say it still stinks, but will get better. The other warning concerns length; my chapters have averaged at about twenty pages, so if you are determined to finish this first bit don’t expect it to end too quickly. Enjoy! And I would love to hear any thoughts on it, including all the editing I need to do, and what parts were a bit hazy.

awoke to the pungent scent of frying tomatoes and dragon fire.

There was no time to pinch back my basil or even tie back my hair, I could already

hear Mel’s mighty bark heralding the danger. I leapt from my little bed and

raced for the door, grabbing my things as I moved. This had become almost

routine since the tomatoes had been yielding fruit, and I was well versed in

the act of drawing on my old holey boots and shirt as I ran. The latch was lifted

in a trice, and the pine-plank door swung open with a smoothness that

brought a sense of joy and fulfillment into my heart. It had taken most of the afternoon

yesterday to strengthen it and repair the hinges; but it was better now because

of something I had done, and I felt a sense of usefulness and strength

in me that had made me first love my farm. As the door gave way, the bright morning

sunlight flooded into the house and allowed me to see what I had to deal with.

I knew from my dog’s noise it would be trouble. But I had no real fear, nature

had a cure for any cause, ill or good, all I had to do was simply direct it.

tomatoes were being hard hit. Four dragons circled above my little circular

patches, their tails flicking out in anger and looking like six-foot snakes. The

sunlight made their bright scales shimmer and gave them a particularly vile

look. But not as vile to me as the row of freshly churned up mud and the

missing wall of trees that had been at the pine forest when I went to bed five hours

ago. It seemed the loggers had been hard at work in the moonlight. I didn’t

mind their harvesting the trees, but why did they have to leave such ugliness

and destruction behind them? If only those of the Halfful Lumber Company would

listen to my suggestions for sustainable harvesting… but it was a forlorn hope

that any would ever listen to me, Charlie Biggton. At least they left me alone

to tend my farm, with only occasional grumbles. The sound of a furious howl reminded me of the trouble at hand and I looked back and my little farm, a

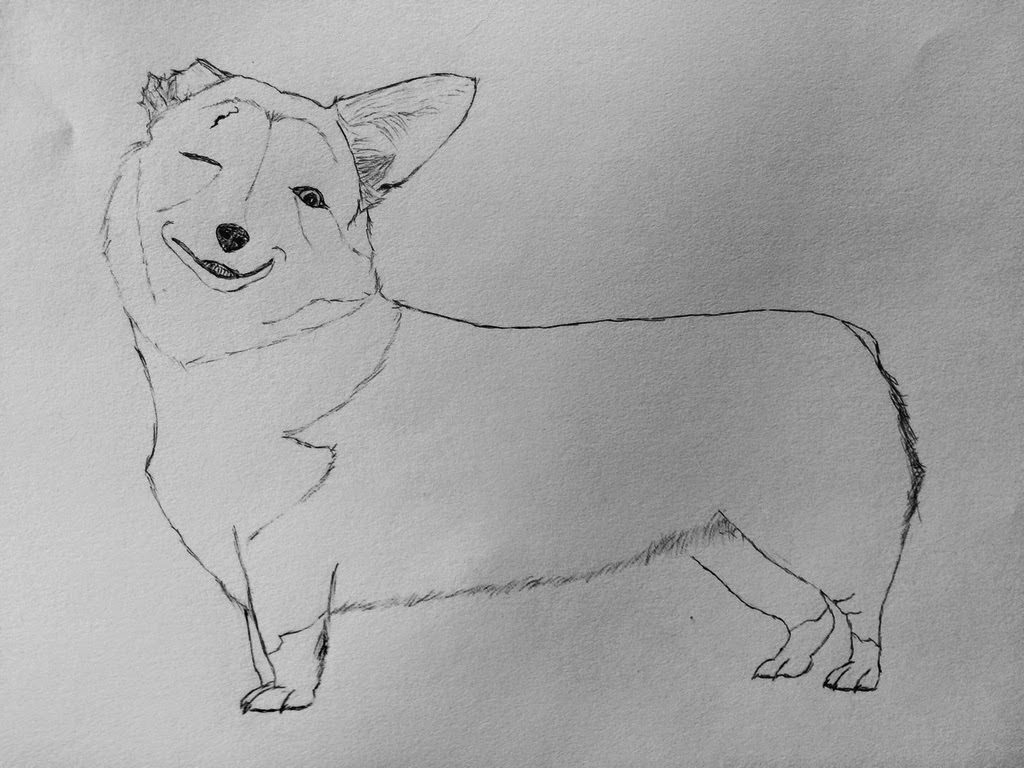

patch of green and beauty in the midst of all the mud and filth. Melawnwyn was

heroically keeping the scaly brutes off the plants, his rich growling-bark

rolling over the fields as he darted back and forth from one tomato patch to

another. All I could see of his progress was a furrow in the plants wherever he

ran, and I admit I laughed at my faithful helper. And immediately felt guilty

over it.

at them Mel the Mighty,” I called to make amends, beginning my race across the

yard towards my trigger pole, “your voice breeds fear in their cold-blooded

hearts! Charlie is on the job. And remember, Harbal Tongly writes, ‘One day the short shall rule the world!’”

The dog growled louder as he heard me, and his speed was such the furrows in

the plants left by his passing began to swing closed almost as soon as they

opened. I reached my pole and paused, studying the situation. This was my

second good crop of tomatoes, and I had learned last year the fat red fruit

brought on the dragons. They were persistently pestilential beasts, and I had

lost all but three tomatoes to them last

year. And my one-room house had been set afire twice from their white hot blasts, though thankfully I was able to put it out and repair the damage.

But this year I had planted my tomatoes in scattered, circular patches and

placed sieves over them, held up by a pole which also held a pipe attached to

my rain reservoir on the roof of my henhouse. The operating mechanism was

simple enough, a valve held back the water, opened by tugging a chain, which I

had thoughtfully numbered so that I knew which chain went to which sieve. The numbers had been a later addition, after I had failed miserably eight times and soaked my faithful Mel instead of the

scaly scavenging dragons. As I watched, a brilliantly green dragon spun about

in midair, and I could see the glint in his eyes as he hunted for the barking

dog that kept him from his juicy breakfast. His miserable fire sack began to

fill.

Mel.” I called, readying my trap. A line of corn that my herald was racing

through suddenly closed, all except one patch about two and a half feet long,

where I knew the dog stood. The dragon spotted it and swooped, the guttural

gagging cough of a pre-fire breath sounding from him. “Ten, Mel!” I yelled,

grabbing for the chain. The dog raced away, springing along the ground faster

than the dragon’s wings could take him. The pest saved the fire for when the

dog was still again, as I knew he would, but kept up his gagging cough in order

to keep it hot. I could see his firesack bubbling and beginning to glow with

the white heat of a dragon’s wrath. A streak of red-orange shot out of the corn

and into the midst of tomato patch Number Ten. Mel, mighty heart, spun around

and faced the dragon, giving it the high-pitched howling bark he knew the beast

hated. I jerked the chain down and heard the heartening gurgle of the rain

water pouring through, picking up the baking soda I had poured into the pipes

last night. A stream of white hot fire spewed from the dragon, driving it

backwards, his black wings pounding the air as he strove to stay in flight. As

it left his throat, the water began to pour out of the pipe. Mel sidestepped

with remarkable dexterity, his one good ear twitching at the furious hiss of

the fire dissolving in midair.

“All praise to our timing, my boy!” I yelled ecstatically, noting not

a single plant had been singed. And one of our foes was taken care of, he would

be exhausted for the rest of the day now, and would seek a high tree where he

could nap and regain the energy to blow out another fire breath. He gave a low

moan as he fluttered weakly towards the dark forest fringing my little spot of

green, and I jeered at him unapologetically. The dragon exhaled the cloud of

smoke from his fire blast, and I noted the white smoke had a red tint in the

light of the early morning sun, a color that made it seem very nefarious. But despite the scent

of decaying plant and animals it left behind, there was nothing dangerous about

dragon smoke. I knew it well, I had inhaled enough of it last year. Mel’s

growling challenges suddenly changed to an irate yapping, and I knew it was

meant for me. I quickly turned my eyes from the defeated dragon and back to our

still flying foes. One, a slim pest of deep green and average size, was flying

hard on Mel’s stubby tail through the cabbage beds. My fellow soldier was

heading towards patch Number Five, and I quickly fumbled for the chain.

Mel, Charlie’s on task again.” I called, and he immediately went back to his

barking growls at the dragons.

was then I heard the dreadful gagging cough behind my head and felt my dreads

stir in a furious hot breeze. I spun around and found myself staring at a brilliant

blue dragon face, as the beast stood reared upon its hind legs to be as tall as ever it could, stretching to reach my meagerly 5’4″. But it was tall enough. Her bright blue tint let me know this was a female, and an angry

one. Her black wings pushed against the succulents I had covering the ground

near the buildings as a fire retardant, her small yellow eyes were wide with

ire, and the firesack was bulging and bubbling. A scream burst from me as I

threw myself to the ground. Chain five was jerked with me as I fell, and I

heard the blast of steam that let me know I had caught the other fire, and Mel

was alright. But the sound was immediately replaced by the roaring fury of

dragon flames searing the air around me.

jerked forwards on my hands and knees, gasping for oxygen as the fire sucked it

all away, and feeling my back beginning to blister. Then I was at the dragon’s

side. I scrambled under her wing and rolled onto her blue tail. She let out a

furious bleating bellow, and I felt the long tail squirming and slithering

under me. A dragon is very sensitive about their tail, and intensely indignant

if you touch it. I jerked out my fork, kept in my jacket pocket for just such

moments, and jabbed the blue scales under me. A great roar of indignation shook the

dragon, and with a mighty flap she lifted into the air, teetering a little

ungainly in her exhaustion and anger. The air filled with her exhaled smoke,

surrounding me with the dreadful stench. I clapped a hand over my nose and

mouth and staggered away from the cloud. A furry body collided with my foot and

knocked me headfirst onto the gravel path winding from the squat farmhouse to

the hen coop. A wet tongue found my nose as Mel tried to apologize. I rolled

over and sat up with a groan. The smoke dissipated and I saw the last two

dragons winging for the forest, evidently finished for the day.

done Melawnwyn the Mighty.” I coughed, laying a hand on my friend’s head. His ear

slicked back in appreciation of the simple praise and a happy pant flew from

his black lips. I smiled back at him and climbed slowly to my feet, groaning as

I felt all the bruises and burns acquired in the morning’s work, considering

our next move. I looked down at my farm worker and smiled again at the

expectation in his one eye. Melawnwyn had come to me two years ago, battered

and half dead, a young starved creature with little left but the breath in his

lungs. The right side of his head had been sliced and burnt beyond repair.

Though the orange fur grew back to cover most of the scars, he would forever

miss his right ear and see only from one eye. I had never learned his story,

and never tried to discover any past owners; nature had its ways, and if Mel

had wandered into my keeping I was perfectly happy that he stay there. Now he

nudged my knee, his stubby tail wiggling as he looked up at me waiting to hear

the word he longed for. I gave it to him.

You’re right, my boy, I think breakfast first, Charlie’s hungry too. And then

we will see about the rest of life. The morning sun only lasts for a scant five

hours, let’s get our work done here before the moons shows their face again and

we have to deliver goods to old Growler Venderbeer.”

monotonous brown and unchanging, muddy slither. There was nowhere to set my

boot without feeling it squelch deep into the sticky mud. The effort of pulling

it back out, and setting it down again, and pulling it out… it seemed to have

been going on for years. I had to forcefully remind myself we had only come

into this region of bare mud some six days ago. My pack dragged on my back and

I shifted it to my right shoulder, mentally running through the contents and

attempting to think of something I could leave behind to lighten the heavy

pull. But everything I owned was in that pack. And I would not willingly part

with any of it, not after having carried it so far. The mud pulled at my feet,

and my legs ached, and I did not want to think of the next step. So I lifted my

eyes from my travel weary feet and turned them on the landscape, trying to find

something pleasant. There was nothing. Only the bare, ripped up brown hills

where majestic trees had once stood. This place was almost worse than the

scorched lands we had crossed to get here. This wasn’t the work of the Rockies,

this was voluntary work of the residents. They might have left a few of the

trees standing for the traveler to rest their eyes upon as they marched over

the long roads. But no, there was only the mud and the dull blue of the sky as

the sun began its downward climb. The afternoon dark would come in an hour. And

the land would look better for it, I thought wryly.

beside my weary feet, I set my eyes on my father’s broad back as he trudged in

front of me. His cloak was muddied, and even his black sword sheath hanging on

his back, usually kept so carefully clean, was splattered with the sticky mud. His

shoulders were stooped, and I felt a pang of sorrow for his great heart. He had

longed so much to find a peaceful place for the two of us to settle in, ever

since Grammy had died and I left her care to join him in his travels last year.

But I had followed that back across the world by now, and found no place to

stop. Through city and outlands, there was no peace for Meagan, or any related

to him. My father was too outspokenly Christian, and too strong-willed to lay

down his knightly service to the king, even though the usurper had now ruled

for seventeen years. And I would not have my father any other way. So I told

him at Clappton, our last stop, as we furiously repacked our things before the

Rockies came for us. I had seen some of the weariness lift from him at my

words, and the strength of battle return to his eyes. He had gotten us out, as he always did, and the light of Christ would still burn through the

Rockies false words by my father’s speeches and our steady work. Yet it was

hard to be always searching and never able to stop.

and I shifted my pack again. Father looked back at me and paused in his even

stride. He nodded ahead and I followed his gaze. The land changed there. A wall

of enormously high pines blocked out every other sight, rising to what looked almost

a mile into the sky. They were such a dark green they looked nearly black, and

I realized it would have been little comfort to the traveler to have left any

of those along the roadway.

said, slinging my water off my back to better use our pause.

fringe of those trees.” Father nodded, his calloused hand rising to point. Then

I saw a stand of rough wooden buildings, set in more of this sticky mud. At a

glance I guessed there were some two hundred residents in the place, and I knew

from the sight of the buildings that not one ever bathed more than once a week.

But it was our last chance at finding a home. And so a home we would make it. I

smiled for Father’s benefit, my eyes still on the wooden buildings.

have growing things near, even if they are a bit dark.” I said. Father’s eyes

softened visibly as he looked at me, and he stood a bit straighter.

swept his staff up again. “Come Corinth, we will find a home here.”

began to follow his back again. The road curved and slithered along, and the

mud only grew worse as we got closer to the town. But it was pleasant to think

of sleeping with a roof over us tonight instead of wrapped in a cloak trying to

keep my hair out of the mud. The effort of pulling my boots up and placing them

down in the oozing brown stuff seemed a little less tiring as the hope of gaining

a pot of coffee surged through me. The sun sank, and blackness fell over the

land, so thick I could no longer see my father’s back in front of me. But I

could hear his squelching steps and gauged my own by the sound. On we moved,

and soon the scent of the stinking mud began to be mixed with the scent of

fresh cut pine wood and, much more glorious, the scent of coffee and cooking

beef. My steps quickened almost unconsciously and I could hear my father’s do

the same. The first moon peeked over the northern horizon with her silver

sheen, and she was bright enough the vast trees began to cast a shadow over us.

broken as I heard other squelching steps move onto the road ahead. Father

stopped with a grunt, and I drew up swiftly, one hand silently pulling an arrow

from the sheaf hanging at my side. Greet all travelers you might meet, but be

prepared to receive a knife-blade in return in these days. I swung cautiously

to the left and looked past the dark blotch of my father. A skinny form

carrying a large bag had just moved out of the trees onto the road. He didn’t

seem to notice us, and strode on with a swinging gate, a whistled song coming

from him. It was a kind of half-a-tune, as if he were searching for a song he

did not fully remember; and I wondered very much that the same kind of

half-memory stirred me as I heard the strains. Something almost remembered,

sweet and gentle, but that I could not grasp. I put it out of my mind, deciding

it must be a tune that sounded like many others, and watched cautiously. A long

low dog, its head no more than two feet from the ground, was trotting at his

heels. It swung our direction and paused, then gave a low growl and bounded off

again towards the vague whistler. Father shrugged his pack up higher on his

shoulder and strode on again, moving a little faster to overtake the stranger.

I trotted beside him, slipping my arrow back in my sheaf, but shaking my

right boot a little to be certain Sticker, my dagger, was ready if I needed

him. The dog gave a growl again as we got closer, and the stranger turned to

look back. He stopped as he saw us coming forward. The moonlight was not giving

off too strong a light, and all I could make out was a vague skinny form with its large pack,

only a few inches taller than me it seemed.

stranger said, in a soft voice that stumbled over itself as if he wasn’t quite

sure he wanted to speak after all. It was heavy with the accent of this Jaspur

Region at the bottom of the world, a sort of slow rolling thickness that reminded

me of the long stretch of mud we had traveled by. “He thinks it his duty to

warn me of… of anything, actually. And announce my coming. And the coming of

anything even…” his voice withered away into a timid sigh, before he spoke

again. “Charlie Biggton.”

The stranger recoiled a step and began to rub one foot nervously against the

other at the sound of my father’s rough voice. “My daughter and I are looking

for a place to stay here.”

Venderbeer’s place. Well, she isn’t actually ‘Growler’ that’s what Mel and I

call her… well, Mel being a dog doesn’t really call her anything… Come on, I’m

going there.” The stranger swung off again, sidling closer to the trees, and I

thought trying to gain a few more feet’s distance from us. He seemed a timid

thing, quite unsure of himself. I found myself thinking of the few brown hares

we had spotted in this region; intent on their own business, and quick to slide

away if they saw you coming, but interested enough to watch you at a safe

distance. None of us said anything. The second moon rose in the south as we

squelched along, and the light began to be a little better as both their silver

sheens spread over the world. But there was still little to be seen of our

guide. Not that I bothered trying to see the rabbit-like fellow, I was much

more interested in speculating on the brew of coffee a place like this might

prepare. We moved steadily closer to Halfful, the town at the bottom of the

world, and our last chance at finding a place to settle. Father had said he

doubted the Rockies had much interest in this area, as they preferred the more

barren lands, and he hoped we would go unnoticed here. But it had been a

doubtful statement, and we both knew the rumor; the Rockies were looking for

something, and were intent on scouring the world for it. It would not be long

before they reached even the bottom of the world, and such little grungy places

as Halfful. For my part, I had small hope of ever going unnoticed with my

father’s outspoken ways, but I had no wish to cure him of it.

may.” Father broke the silence. Our guide jumped rather high at the sudden sound, but he nodded in a sort of vague friendly manner.

over in a month or so, and makes the place a little nicer. The people here…

well, they are here. And they don’t particularly mind if you are too, as a

general rule. At least if you leave them be.”

was surprised. He either knew nothing of Christianity, or more than most of

humanity to ask that.

muttered cheerily, and then went on with great hesitation. “You might, ah, not

want to speak of it too much. They don’t particularly like hearing about ideas

and… I don’t think they would like yours.”

He laughed, a sort of soft choking kind of sound, that was very odd but fairly

pleasant.

think much of anything.” He answered. “I take my cue from nature. She lets

everyone be what they will, and allows them to serve their own purpose.”

Sunday to hear of our purpose?” Father asked.

his hand vaguely at nothing in particular. But I had heard many such answers

and knew how to gauge them now. This man would not come. A wooden-plank

building loomed up in the dark ahead of us, and as we squelched around it I

realized they were much larger then they had seemed from a distance. This

square box must be some two stories, and wide enough for three families to live

comfortably in each story. The buildings were placed symmetrically along the

muddy streets, one on each side every five yards, and some were larger than the

first I had seen. Many had a yellow glow of candle light shining from them, and

as we walked well inside Halfful the glow began to supplement the moonlight. I

glanced at our guide and was surprised again, not very

pleasantly. He was even skinnier then I had first thought, and had long strings

of matted hair hanging past his shoulders, looking remarkably like dead, furry

snakes. Judging from the color of his scrubby beard they must once have been

the same wheat-like sheen. But now they were a dull brown, and even gray in

places. Not naturally, or dyed either, but simply from dirt and grime. I

stepped a little closer to Father and turned my eyes back to the buildings we

were passing, forcing myself not to frown too heavily. This Charlie turned onto

another street and pointed ahead, turning to smile at us. At least his smile

was pleasant enough, and his brown eyes were clear. Though they shifted away

from a direct gaze. He was pointing out another of the pine plank square

buildings down the street. It was dilapidated, recently patched

up with new pine boards, and a sign hung from it that bore the words,

‘Venderbeer’s; the Best Beer, Far and Near.’ It did not look promising. But I

could smell the beef and coffee I had scented earlier, and did not give up hope.

Our guide pulled open the plain plank door and stepped aside, holding it open

for me, smiling vaguely at his muddy boots and motioning his orange dog to stay.

It was a small gesture, but one that none but my father had paid me for a full three

years. I nodded him my thanks as I stepped through, being certain I caught his

eye so he saw it. Any who took the effort for such courtesy should know it was

appreciated.

burning fire struck up at me and drove away the cold stench of the muddy out of

doors. I flung my cloak hood back gratefully and stepped down into the large

room. It seemed to take up a full half of the large building, filled with

sturdy but roughly made pine tables and benches. Twenty-four people looked up

as we entered; two well-built barmaids, a bulky man behind the well-stocked

pine bar, some twenty very large people at various tables, and one big woman in

a cap and apron that I took to be the owner with the way she eyed us. All but

two of these people could match my father in height and size. It seemed our scrawny

guide was not the normal build of those in Halfful. Although he did seem rather

normal in his rough unhandsome choice of clothes. The big woman’s gaze shifted

behind us and she nodded.

it.” She growled.

Charlie Biggton murmured, moving past us in a timid shuffle. He sat a very worn

pack on the large bar, and undid the drawstring with a gentleness that was

almost a caress. Father began to move deeper into the room towards a table near

the fire, and I followed him willingly. ‘Growler’ shoved our guide aside

roughly and jerked the bag open. Her large hand slid inside and came out with a

potato. She began examining it as I sat down with a contended sigh and slid my

booted feet a little closer to the fire. A grizzled old man leaned over and

spoke to Father, but it was only an inquiry as to the state of the roads, and Father’s

inquiry as to the state of the beds here, and I was not much interested.

Instead I watched the scene at the bar. The large growling woman and the dreadlocked

Charlie Biggton seemed the only two people of even mild interest in the room;

all the others held the same surly foolish look and were disposing of their

food and drink without much talk. She shook the tuber under Charlie Biggton’s

sharp nose, a frown cut deep into her face.

guests don’t take to dirt on their vegetables, Hairy.”

shock breaking over his face. “Say it is not so! Dirt on a root vegetable? However

did that get there?”

it be if I stopped buying your stuff?” the woman growled, one eye nearly

shutting in a leer that was hideous to see. Charlie Biggton smiled in his vague

way and began to empty the sack onto the bar, with the same gentle motion I had

noticed earlier. I had the idea he cared more for the vegetables he was leaving

behind then any person in the room.

food but from me?” Charlie Biggton murmured. “I will clean them before I bring

them next time, if you wish it.”

again. She swept past him around the bar and disappeared into the kitchen. Our

guide leaned against the bar and began to whistle vaguely again, but his eyes

sought my face. He looked away in confusion as he noticed I had noticed him. I

turned my attention back to father. He had managed to get the old man to talk,

and had already learned of a small house set just on the edge of town that

might be let to us for a modest enough fee. My heart rose at the thought. Even

if it only lasted for a few weeks, it would be very nice to have a house of our

own. The woman swept in again, slapped a small coin purse in front of Charlie

Biggton and swept on towards us without a glance at her vegetable supplier. She

planted herself in front of our table, her large hands on her larger hips, and

a frown on her whiskered face.

She asked.

The old man at the table next to us spoke up. “But I suppose they will settle

for one of your flea-bitten beds for the evening, seeing as how the Jaspur mud

is out.”

woman snapped and then looked back at us.

Father said, in his deep voice.

have that.” I added. The woman nodded and marched away. Charlie Biggton and his

pack were no longer at the bar, I saw after she had moved her bulk. I did not

give it much thought. I did not give anything much thought. The pleasant feeling

of having arrived after a long journey was settling over me. I was perfectly

content simply to sit, with my boots towards the fire, watching the flames

dance and feel the warmth seeping into me, and know that supper was coming

soon.

hard work in the mud, and I turned off it as quickly as I could, into the

forest. The black pine needles that covered the floor managed to find the hole

in my left boot, but it was still more agreeable then the mud. And I liked to

walk among living things, even when they were so large and dark. Mel ran on

ahead, busy with his snuffling about under the enormous trees. What would it be

like to have the nose of a dog, and be able to smell things as they did? Would

I enjoy the scents that Mel seemed to, or would they still seem as odious to me

as they did now? If they were still foul to my mind, it would not be nice to

have a dog’s sense of smell, as the smells would only come to me all the

stronger. But I would be able to smell lovely things better, like sunflowers

and Earl Grey, and that would be quite nice. I yawned and walked a little

faster. The sun would rise again in a scant four hours, and it would be well to

get at least an hour or two of rest before starting in on the next five hours

of sunlit work. A smile played over my face at the thought of sleep and, I

admitted to myself, at the thought of the dreams that might come with it. There

was a sweet face of a woman that came sometimes as I slept, round, with red

cheeks, and a gentle smile the like of which I had never met in life. She would

sing to me, a lullaby that I half-remembered when I woke and always tried to

recapture as I worked about my fields or wandered about. Perhaps I would meet

her again tonight. I struck my path, worn down in the four years since I had

claimed my farm land and begun to build and work it when I was sixteen. I got

on faster after finding my little snaking trail. Soon the trees began to break,

and I heard the sound of the hens clucking and shuffling about in their house

as they began to settle in for sleep.

into my little spot of cultivated land and felt happy delight and peace spread

over me. The tomatoes were shining in the moonlight, the lavender and thyme

filled the air with their delicious scent, and the sound of the lettuce leaves

and corn stalks shifting in the slight breeze sounded beautiful. This was one

little spot that grew and had usefulness, and green, and beauty to it. All

around us was bare mud or choking dark trees. But here the ground was

revitalized and yielded up good things. And I had built this, in all its green

usefulness. A sense of pride, and the comforting thought that not all my life

was a waste, came over me again as I stood in the moonlight observing my little

domain. But it needed tending to, and I would do it better with a little sleep.

I called for Mel and stooped to go into my house, my herald announcing my

entrance with a guttural bark as he slid past my leg. I lit the lamp and busied

myself for a few minutes checking my seedlings sprouting in the terrariums

scattered around the single room. All had sufficient water, and there were four

new arugula sprouts peeking through the black dirt. I gathered a few castings

from the worm box shoved under my small sink and worked it around the delicate

seedling. Then I pinched back my basil hanging in pots above the table, checked

my Earl Grey stash, found it nearly empty, and decided to wait till I could

trade a few hen eggs for milk to use the last of it. The thought of eggs made

my stomach rumble and I quickly cracked a few into my small cast iron skillet,

scavenged from a castoff junk pile, scrambled them up with the last crumbles of

cheese, some cilantro and basil, and dropped onto my small bed, sandwiched

between my bookcase and the table I had scrounged from the outcast boards of the

lumber mill’s scrap yard. Mel leapt up beside me, and I dutifully gave him a

corner of my dinner, though my stomach growled at me in protest of the action.

A sense of happy peace settled over me. I let it stay unchallenged for a moment, and then

reached for my latest book.

Follsom, trading him my eggs and some of my other wares for his books, and had

recently acquired a copy of the history of the early €lænğał Kings. It was well

used, and as I cracked it open a page fluttered out onto my dusty floor, but I

found where it went and was still delighted with my find. History had always

fascinated me, almost as much as the old poets delighted my heart. And I loved to learn of the strong old kings, set up a thousand

years ago after the last major religious war. The €lænğał Kings, just and wise,

wise enough to love the arts and peace more than war. They were a strong breed

of men, and women, and for years and years the kingdom had existed on in peace

because of their steady rule. It was a pity they had finally been thrown down.

And in my time too, when I was but three. I wished it

had not happened in my time as I finished my eggs and read of Umber the Magnificent,

quelling the Kel that had tried to overtake the kingdom some five hundred years ago. He was truly

magnificent. But my eyes were closing on the tale of his son, Horotol the

Black. It was time to get a bit of sleep while I could. I sat my book down on

the shelf, and my cast-iron pan in the sink, dimmed the lamp, and then flopped back

on the bed. Mel settled beside me with a contended sigh and I smiled at him, my

mind on the strength of the €lænğał Kings and their deeds of old.

strong, stern man as that Meagan thinks he needs more then what he can make for

himself?” I asked Mel, scratching him fondly behind the ear. He groaned a thank

you in answer and rolled onto his back so I could rub his muddy stomach

instead. “It is a strange thing, Mel, that so many think they need more then

what they can feel and see. And if you do decide to worship something, you have

two choices; you can either worship rocks and the fire that makes them glow, or

a God that no one has ever seen who died and came to life again on a strange

world that no one can prove exists. Both religions are equally ridiculous. I

wonder what the daughter thinks? Well, what she thinks of her father’s

religion, it was obvious she didn’t think much of me. Mel… she looked familiar.

Unaccountably so, because I am certain I have never met her. But still, there

was something about her face… I’m sorry she caught me looking at her though, I

doubt that helped her think well of me. But no one ever thinks much of Charlie

Biggton. But they like what we grow, Mel. And so do the dragons. Those pests

will be back again at dawn’s light, we had best get a few hours sleep while we

may.” I said, curling onto the thin blankets as I did. It felt very good to lay

still, and a contented sigh broke from me.

his feet, his one ear perked high and a deep throaty growl siding from

him as he stared fixedly at the door. That was a growl he used seldom, only

when he noticed something of real danger. He leapt off the bed and was at the

door with one bound, snuffling at it with every hackle raised. I slowly rose

and crossed to him, pulling the door open reluctantly. I wasn’t at all sure I

wanted to know what was out there. I only saw the dense darkness of an overcast

moonlit sky. Mel stayed near me, pressed against my leg as if he needed the

comfort, and it did not help my heartbeat slow to its usual regular pace.

Melawnwyn the Mighty was ten times braver then I, and it frightened me to see

him frightened. But I swallowed the lump in my throat, unhooked the lamp from

the low ceiling, and swung it out the door. The yellow circle of light it gave

off only illumined the succulents covering the ground around the house and the

gravel walkway leading to the chicken coop and fields. But I… felt something.

It was odd, not one of my five senses could register something strongly enough

to tell me what it was, but there was something different about the outside

world then what it had been when I had come inside. Perhaps a faint scent.

voice seeming very thick. I stepped outside, feeling my heart pounding and my

senses tingling with the effort of trying to notice everything at once. Mel

stayed pressed against my ankle, occasionally giving off his throaty growl that

told me he felt real danger very near. We made a quick circuit of the land. I

found caterpillars eating the garlic plants, and spotted the red eyes of a fox

contemplating trying to crack into the henhouse again. But there was nothing

else out. And yet Mel stayed right by my ankle, and every few moments I felt a

tremble run through him. Never had my mighty Mel shown such symptoms around me,

and my heart was far from easy. But there was nothing else to be done, and even

if I found whatever intruder was worrying my furry friend, what would I do?

Scream and throw the lamp at him, I supposed. I sighed and ducked through the

door into the house again, grateful for the solid walls around me. I shoved my

chair up against the latch, and drew the shutters closed before lying down

again. Mel stretched out beside me, his ear still alertly listening, but none

of the trembles shaking his sturdy form. I threw an arm over him comfortingly

and let exhaustion take me into the realms of sleep. As I began to give into

the comforting darkness, I thought I smelled a slight stench of smoke, and it confused

me. It wasn’t the dragons white smoke, that was certain. I decided the mill

must be working on something new, and thought no more of it; but a vague sense

of unease haunted my dreams, and the sweet face of the woman did not come. Something

black and nasty oozed into my slumber. It was large, and shapeless, and began

to cover me, so that I could not breathe.

sharp teeth nip my nose and sat up with a cry. I was soaked in sweat, horribly

dizzy and weak. My throat was immediately flooded with a dense black smoke,

oily and tasting foul, as if it were made of the ground up remains of rotted

rodents. I reeled on the bed, unable to see anything, my senses so clouded and

overcome it was nearly impossible even to cough. It was only a desperate sense

of survival that got me to move, rolling onto the floor and crawling towards

the door. My limbs were heavy and slow, and my head swam horribly. Every breath

brought in more of the smoke, and less and less oxygen. Something was clogging

my airways. I began to register the noise as I crawled; a roaring and crackling

was just above me. A fire was eating up the roof. A little more sense returned

to me, and I noticed the heat. At once it nearly overwhelmed my already

overwhelmed body. The house was a burning oven, filled with the deadly dense

black smoke and the roar of the hungry flames. My strength faltered and I collapsed,

lying gasping on the ground. I had not even the sense left to feel terror of

the flames.

me. The soft fur of his head bumped my chin once, and then again. A whine, soft

and desperate, came from him. Then I felt fear. I realized my mighty warrior

could not open the door on his own. Mel would burn helplessly inside this foul

smoke if I did not let him out. I was terrified at the picture of his writhing,

burning form that came into my mind, and it was the one thing that could have made

me move again. I forced myself to my hands and knees, jerking forward and fighting

to find a breath of oxygen in this crackling oven that had been my home. Black

smoke swirled everywhere, but as the fire burned through the roof it began to

pierce even the oily smoke and allow me to see by its dancing red light. The

pine chair was still pressed against the latch, though it was already burnt and

charred as fiery debris fell on it from the burning roof. I staggered to my

feet, knocked it away with a choked cry, and pulled open the door with the

remains of my strength. More of the black smoke poured in from outside.

Melawnwyn sprang away into the blackness. I fell to the ground and rolled away

from the house, my weak selfishness wishing my friend would stay near me. It

felt very hard to be there alone. I tried to crawl after him, but there was too

much smoke in me, and not enough oxygen. I was fainting, and with each breath I

drew in more of the poison. With a great effort I opened my stinging eyes and

looked out at my farm.

flame devoured the green. All my work was being eaten away, and soon nothing

would be left but black ash that would be blown away in the wind. I wheezed in

another breath and closed my eyes, curling on the ground and helplessly feeling

the burning heat of the flames beginning to lick at me. It hurt. But sorrow

overshadowed my fear. I would be blown away with the rest of it. Charlie

Biggton, gone with the breeze, nothing left behind of his life but ashes and

smoke… None would even mourn me. My mother might remember me, for a few years.

Lying there coughing and choking for a breath, desperately afraid and alone,

the lullaby came to me again. It was sweet, and clearer than ever before, a

beautiful tune that breathed memories of a gentle love and half-remembered

times of sunlight and green. I knew I was fainting and would not wake again. I

welcomed it, letting my mind drift further into the dark, hoping I would

perhaps glimpse the gentle woman before I fell into the oblivion of the dead. But

even as I longed for it, I felt a great, terrified thought that there might be

more; what if it wasn’t oblivion I was falling into? Terror of death itself

gripped me and in its driving force I dragged myself a few more feet from the

burning house. But still the black smoke followed. It wrapped itself around me,

a malevolent, foul blanket of poisonous fumes, swirling and dancing around me. I

could feel it clogging my throat and keeping what little air there was away

from me. The sound of the flames burning away my life seemed to laugh at me, and

I lay and choked in the smoke. I would not let my eyes close again. Fear of

what might confront me if I let go of life was stronger even then my failing

body and I forced my eyes open.

face for an instant and I could see. Something moved. Off near the fringe of

trees, something watching the flames moved. I thought of Mel and relief flooded

in; perhaps he had come back for me! The black smoke swirled into my face and I

could see nothing but its oily foulness. But as if taunting me, it shifted away

again for a brief instant to let me see the world I was leaving. And then I saw

it move again, and knew it was coming closer. And it was gray, and the shape of

a man, not Mel. The smoke filled my vision, blinding, and choking what little

breath I managed to gain from the burning air. But I felt the someone still

coming closer. It was the same feeling I got when I harvested my tomatoes, and

knew the dragons were watching maliciously from the woods, just waiting to

swoop down and wrest my basket full of red fruit away. I wished whoever was

watching me would stop, and let me die in what little peace such a hot, painful

death would allow. But death… death! I wasn’t ready. Again I fought my eyes

open, struggling to find the strength to get a few more yards out of this smoke

and heat. But this time I could not move at all, and could not recall my mind,

or even call out.

suddenly to the side as something stepped through. I looked up,

desperately trying to plead for help, and knowing there was nothing I could do

to even let anyone know life still clung to me. And then I saw the form

standing over me. Horror chased away what little strength I had left, and I fainted.